At first glance, the Dadaism art movement can feel like a joke that no one bothered to explain. A mustache drawn on the Mona Lisa. Nonsense poetry read in a language no one speaks. A urinal turned into an art exhibit. It’s chaotic, ridiculous, even childish — and that’s exactly the point.

Dada wasn’t just an art movement. It was a response — a gut-wrenching, sarcastic, furious response — to a world that had completely lost its mind.

When Dada emerged in 1916, Europe was in the thick of World War I, a conflict so vast and horrifying that it shattered any lingering belief in progress, rationality, or the so-called nobility of mankind. Millions were dying gruesomely in muddy trenches, all because of petty political squabbles and a blind allegiance to tradition. Civilization, which was supposed to represent the pinnacle of reason and enlightenment, had instead orchestrated the greatest disaster anyone had ever seen.

In the face of that, how could artists go on painting pretty landscapes or sculpting idealized figures? It would have been obscene. The world was absurd — and so, Dada declared, art must be absurd too.

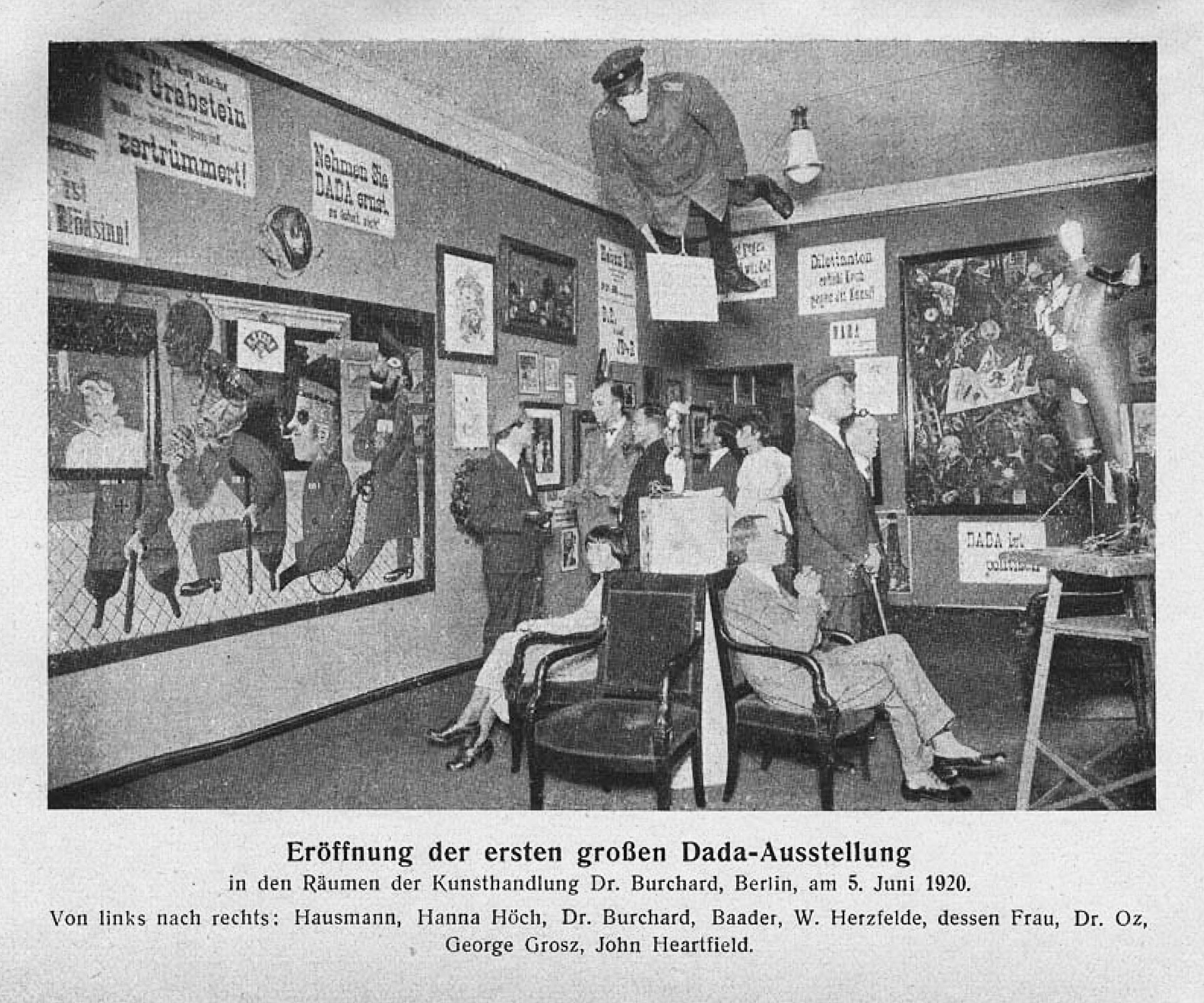

The movement started in Zurich at the Cabaret Voltaire, a chaotic nightclub where artists, writers, and performers would gather to make a joyful, angry mess. They threw logic and traditional aesthetics out the window. They embraced randomness, chance, and humor. They created works that didn’t make sense and didn’t want to make sense.

Marcel Duchamp’s infamous Fountain — the urinal he signed “R. Mutt” and submitted to an art show — wasn’t about craftsmanship or beauty. It was a dare, a confrontation: “If society can declare war a noble cause, why can’t I declare this urinal a work of art?”

Dadaists weren’t trying to offer solutions. They weren’t optimists. They wanted to tear down the idea that the structures humanity had built — whether governments, institutions, or even art itself — had any real meaning. They exposed the hollowness beneath the surface, and they laughed bitterly in its face.

In that sense, Dadaism wasn’t just art about war; it was a form of protest against the logic that had led to war in the first place. It rejected nationalism, materialism, and any blind faith in authority. It was chaos fighting chaos — a mirror held up to the insanity of the times.

And yet, despite its seemingly random and ephemeral nature, Dada left a permanent mark. It paved the way for Surrealism, Abstract Expressionism, and even much of the conceptual art we see today. Its legacy is a reminder that when the world stops making sense, sometimes the most honest thing art can do is stop making sense too.

In the end, Dada was a scream disguised as a joke — and maybe, at that moment in history, it was the only sane response to an insane world.

Works Cited

- Dempsey, Amy. Styles, Schools and Movements: The Essential Encyclopaedic Guide to Modern Art. Thames & Hudson, 2010.

- Elger, Dietmar. Dadaism. Taschen, 2004.

- Hopkins, David. Dada and Surrealism: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press, 2004.

- Richter, Hans. Dada: Art and Anti-Art. Thames & Hudson, 1997.

- Tzara, Tristan. Dada: The Dada Manifesto and Other Writings. Ed. Robert Motherwell. MIT Press, 1974.

- Ades, Dawn. Dada and Surrealism: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press, 2004.

- Hughes, Robert. The Shock of the New: Art and the Century of Change. Knopf, 1980.

- Breton, André. Manifestoes of Surrealism. University of Michigan Press, 1969.

- Whitford, Frank. Dada: Art and Anti-Art. Phaidon Press, 1999.

- Rainer, Peter. The Spirit of Dada: A Critical Analysis. Oxford University Press, 2015.

- McCormick, John. Dada and the Politics of Art. Cambridge University Press, 2012.